The night in the bus is magnificent. Sometimes I wake up briefly, gripped by that short, irrational panic that the whole bus might just tip over, as if the darkness outside suddenly gained weight, but all in all, I slept. This would be unthinkable for me in a regular bus, where ten hours stretch into a trial of endurance. This time, it didn’t. When we arrive early in the morning in Trichendur, I am a little tired, but in a soft, good kind of way. Willem Jan’s Indian family picks us up and welcomes us with warmth and open arms. No hesitation, no careful testing, just this quiet, self-evident: you are here. So you belong.

In the nearly two weeks we spend here, I get to experience different aspects of rural Indian life in a way that would never otherwise be possible. Walking through dusty lanes, hearing the rhythm of daily chores, feeling the sun on my skin as it warms the earth and the people alike, I am allowed into moments that are intimate and ordinary at once. For this, I am deeply grateful.

The first thing I get introduced to is the Indian love for good cooking. Akka — “big sister” in Tamil — Kalyani guides me, step by step, into the South Indian kitchen. Not by lecturing, not by explaining, but by repetition, by showing, by letting me follow, by letting me taste. Idli — perhaps best described as rice dumplings, though that barely captures them. Soft. Warm. Almost cloud-like. Dosa — ultra-fluffy, paper-thin crepes made from rice and split black lentils, leaving their French counterpart far behind. Chapati — like wheat tacos, but without oil, warm from the fire, pliable and alive. Puri — wheat, but fried, golden little pillows of air. And then the sides. So many. So varied. Chutneys, Sambar, Kurma, vegetables in spices my body understands more than my mind. And then, my friends, Kalyani’s special noodles: yellow, soft, gently spiced, a small, warm heaven on a plate. It’s the only dish I always tend to overeat. Everything was delicious, but that… hmmmm.

One evening, Akka Tangham shows me, while we sit together on the floor, how to eat with your hands. Only the right hand. That is clear. The left is considered unclean, used for washing after bodily functions. Eating is pure; only the “clean” hand touches the food. Sambar is poured over the rice. You mix. Go all in. All those childhood dreams of playing with food, suddenly not forbidden, but right. Then some of the sides are added, maybe a little Chutney, maybe Kurma. You try to make a small heap, place it on the tips of your four fingers like a little shovel, and push it into your mouth with your thumb. What sounds breezy and easy is actually something you need to practice, especially when you’re in a very local place, surrounded by people who have never done it any other way. And yet, nothing is warmer than the broad smile of an Indian woman when half of your rice falls back onto the banana leaf. No mockery. Only joy. Only: you’re learning. That’s enough.

And in the warmth of these kitchens, I begin to sense that love here is not just a feeling — it is a practice, a rhythm, a way of being that binds family, friends, and strangers alike.

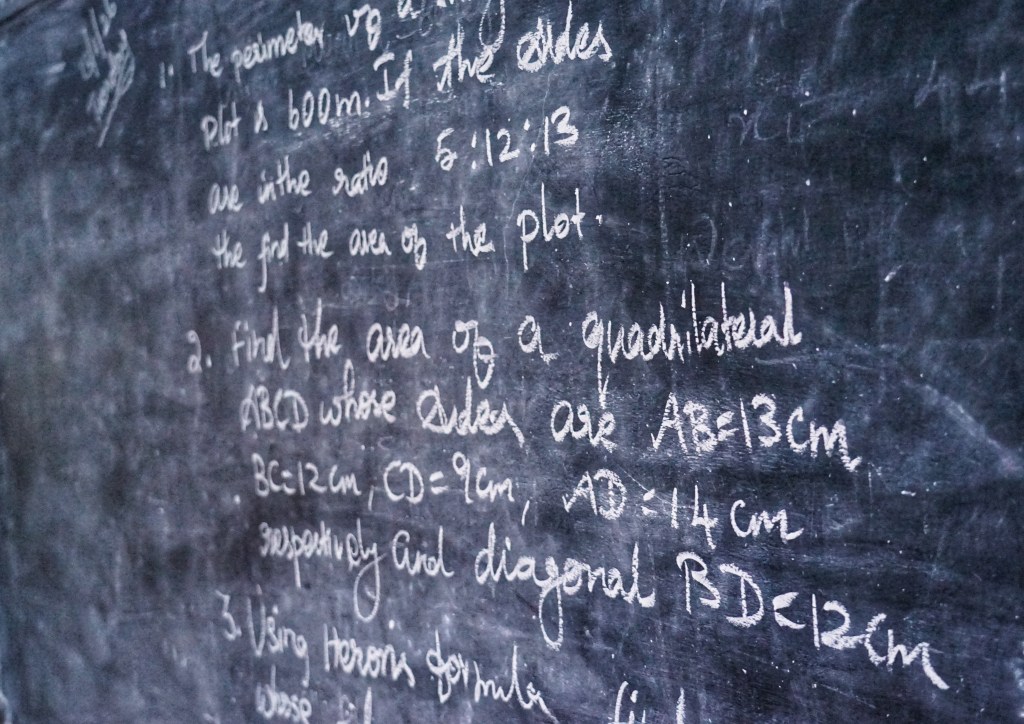

The sense of being allowed inside, doesn’t stop with food. Gradually, the rhythm of the community reveals itself. Starting with the house complex, where the living area sits right next to the school of AID India. I learn about its history, about how sixteen years ago there was nothing here at all, just bare land and ambition. The school itself is bright, orderly, full of life; classrooms lined with simple desks, walls painted in soft colors, children sitting attentively in neat uniforms. Uniforms — something I dreaded when I was young, because I liked to express myself through what I wore. But it also drained energy, and there was always the unspoken pressure of ideals, bullying, comparisons. One morning, I ask my Indian tangachi — little sister in Tamil — Mariamal, as she braids her beautiful hair and prepares for school, if she likes the uniform. She looks me straight in the eyes and says, without hesitation, “It makes everyone equal.” I am stunned by the clarity of that statement.

Another project of AID India brings us to the orphanage Island of Hope in Virudhunagar. I had never been inside an orphanage before; my imagination had been shaped by Oliver Twist and documentaries about Africa, images of hardship and sorrow. What I find here has nothing to do with that. As our car rolls into the parking lot, nineteen shining faces of girls greet us, wide-eyed and bright. As we step out, they pop balloons over our heads, spilling confetti in the air. We are invited to eat, and we sit with banana leaves in front of us, mushroom Biryani, Gobi 65, rice, finishing off with ice cream. Then the girls take me by the hands and arms and lead me through their home. First, the rooftop, where I see the city spread out below us. With shining eyes, they point to the nearby medical center. When I ask who wants to be a doctor, three of them shout with excitement. Then they show me their sleeping area — one room, walls lined with shelves holding all of their belongings, mattresses rolled on top. Each night they lay out their beds side by side on the tiled floor and sleep together. One girl pulls me to her shelf, and to the cheers of the others, she draws on my forehead: a black dot, an orange dot, a line in gray. Black for grounding, orange for vitality, gray for transformation — a small, private map of spiritual meaning. Then I see where they wash and use the toilet. It is simple, but clean. The same bucket shower that I will soon come to love.

Even here, in the simplicity of this orphanage, love is present: in the touches, the small rituals, the teachings, the protection. It is a gentle, pervasive force, carrying these children through a hard life, shaping joy out of scarcity.

Leaving the orphanage, I am filled with a quiet, strange awe. It is not the kind of sadness or deprivation I had imagined. And still, I cannot forget that this is hard life. What does it mean to be an orphan girl in India, to navigate a world that is already difficult for children, and even more so for girls? Across the country, millions of children have lost one or both parents, and only a tiny fraction ever enter the formal adoption system — while vast numbers grow up without the security of a family at all. Many orphaned children are vulnerable to neglect, lack of education, malnutrition and precarious health because resources and opportunities are unevenly available and often scarce outside institutional care. Girls in particular face heightened risks: they are more likely to drop out of school early, to be overworked, and to face threats of exploitation or abuse, and given prevailing gender inequities in society, their path to autonomy is even steeper. And yet, despite all of that — despite these structural hardships that shape their lives — this place feels joyful. I carry with me the bright eyes, the laughter and the small celebrations of everyday life. It is a world I had never known, and one that will quietly stay with me long after the car drives away.

Family in India is not just a hollow word. It is full of care and love. But it also means commitment and expectation bound in tradition shown in all kind of ritualistic appointments.

The first so called Function I attended is a puberty ceremony for a young girl, marking her first period. The event is held in a large tent in the family courtyard, filled with women and children in bright saris, gold jewelry, and fresh flowers in their hair. Rows of chairs for the elders, a raised platform for the guest of honor, and photographers moving carefully to capture each moment. The girl, glowing, is the center of attention, receiving blessings from all around.

I stand among the women, sweating from the heat, aware that I too will be in the photos. I feel a moment of panic and quietly step aside, only to be gently guided by Akka Uma, who never leaves my side. When we return and go up the platform, I smile at the camera but keep my gaze soft, offering a hand to my heart in a gesture of blessing to the girl. After the photos, we descend the steps together and sit in the back, observing the women as they organize the feast. Large cooking pots, polished and steaming, held rice, sambar, lentils, and spiced vegetables. Women moved rhythmically, scooping food onto banana leaves, a dance of hands, laughter, and whispered instructions.

Another ceremony I participate in is a pregnancy Function, celebrating the forthcoming arrival of a child and the mother-to-be’s return to her parents’ home for birth and six months after. The event takes place in a decorated building. Women bring baskets of gifts, flower garlands, food, and armbands. I am invited to hand over armbands in a basket, a small act of blessing. Later, together with Peter and Willem Jan, I help tie the armbands gently around the wrists of the bride-to-be, smiling and speaking softly, aware of the sacredness of the gesture.

Being part of these Functions, even as an outsider, felt like stepping into a living tapestry of care and belonging. Every movement, from the careful draping of saris to the measured scoops of rice onto banana leaves, carried meaning. I am mesmerized by the rhythm of it all.

In India love is felt in the abundance, but also in the spaces in between. For example, when Manakkam, one of the school bus drivers, takes a day off to drive Kalyani, Willem Jan, and me to Kanyakumari, his phone starts ringing twenty minutes after we leave the school grounds. Again and again. Parents asking what happened. If he is sick. Or if something else went wrong. Even a pupil calls, in that high-pitched voice that only children have, asking if he is alright. Manakkam has been driving the same route for fifteen years now, since the very start. Can you imagine this amount of love and care if you miss just one day of work? Can you feel it? I almost cry out of joy.

I realize that love in India is both grand and minute.

Felt through the moments when Akka Uma smiles lovingly at my newest sari draping attempt, cautiously and patiently showing me again what I missed, what I could do better, while reassuring me that my newest attempt wasn’t too bad. Through a joke from Peter about my disgusting cough syrup, calling it Grappa, and by that making it a bit less awful. Through the big smiles of little Mario and Joseph as they play with plastic figurines, inventing the wildest stories with absolute seriousness, and yet complete joy.

I can feel the love when I get sick again. The coughing now turned into a bloody mess in the middle of the night. So, again, I go to the doctor. Something that in the Western world — or maybe just in my world — feels very personal, something you might share with a partner, maybe with friends, but not openly. Here, if one gets sick, everybody is in it with you. Being sick is not an individual experience. Not that everyone suffers alongside you. No. They take it seriously, they take care of you with their traditional herbal wisdom, but even more with their infection’s joy and laughter.

Even sickness is met with love, in care, in humor, in attention. It surrounds you, lifts you, carries you back to life before medicine ever could.

In the end, I feel it everywhere. Love is woven into the air, into the streets, into the hands that feed, guide, and laugh with me. It fills the cracks of my heart with its sweet, scented warmth, mending slowly, gently, without force. And then, in that quiet completeness, I know: it is done.

As the train rattles through the countryside to our next destination, the rhythm of the wheels echoing across the fields, it is as clear as the sky above. My heart has arrived too.

I am in love with India — not just the land, not just the people, but the life that pulses in every corner. I am home here, in its chaos and its tenderness.

If you feel like responding, I’m listening.