This not simply a story about two of Indias hill stations. It is a story about the difference between looking and being shown. Between landscapes you consume and landscapes that begins to speak back. About anger and tenderness sharing the same bus seat. And about wages counted in rupees and wealth measured in generosity.

We wanted to go to Munnar. That was the idea. Into the mountains. To the rolling hills. The tea plantations. In my head I had already framed the most beautiful photo motifs. My mind keeps insisting: I want to go to Munnar. Willem Jan and I even start looking for places to stay, but it turns out to be surprisingly difficult to find something that feels right. Call it superstition, but whenever this happens I begin to wonder whether it is meant to be. This time as well. And it turns out: no. Even if my mind still whispers, but I want Munnar, I feel no pull towards it. Neither does Willem Jan. So we decide to first visit Kochi. What I do feel is a pull towards the mountains, towards cooler air. So I start researching whether there might be something mountainous along our route — and there it is: the Nilgiri Hills rising up not far from Coimbatore, which lies directly in our path. The “Blue Mountains” — stretch across roughly 2,500 square kilometres at the junction of Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Karnataka. They are part of the Western Ghats, a UNESCO World Heritage biodiversity hotspot, and home to the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve, India’s first biosphere reserve. Shola forests fold into rolling grasslands, eucalyptus and tea plantations, and higher up the air turns sharp and almost alpine. Elephants move through these hills, as do boars, leopards, and — with a bit of luck and a lot of patience — the elusive Nilgiri tahr. For Tamil Nadu it is a vital water catchment, climatic buffer, place of agriculture, tourism, indigenous cultures, and one of the state’s most important ecological lungs.

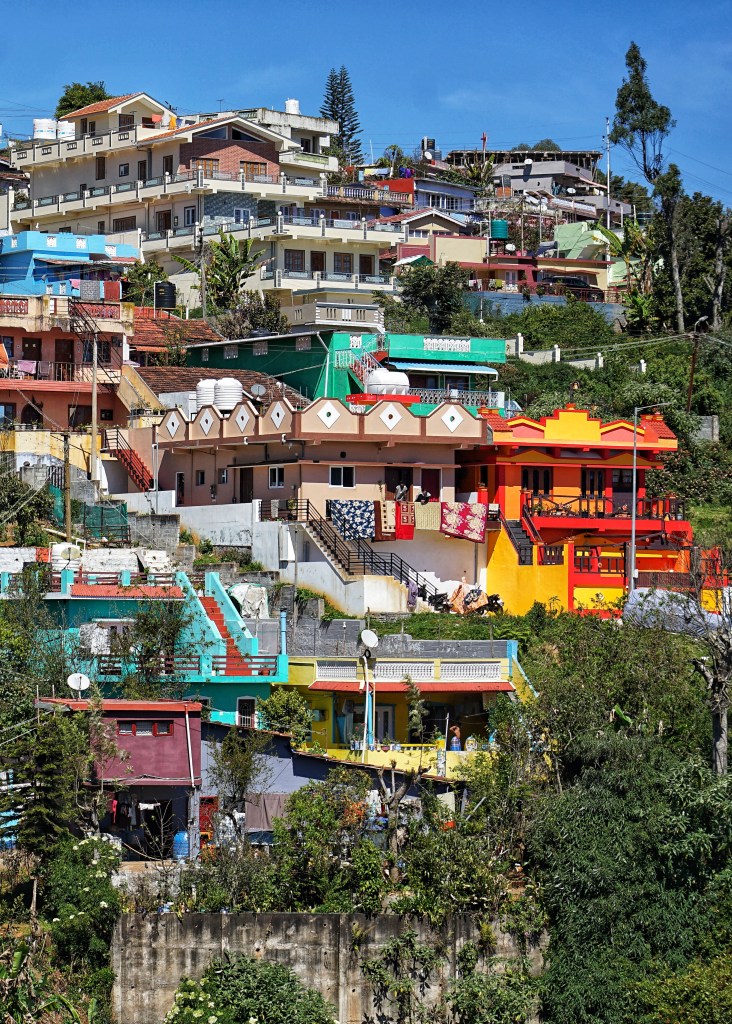

Perfect. That feels right. Willem Jan goes into the whole organization again and in no time we have a new travel plan: We take the local bus up to Ooty. Hairpin bends, narrow roads, a climb that makes the engine scream at every incline. The driver navigates it all without the slightest twitch. All the normally blinking little indicators in the cockpit — none of them work. We move slowly, steadily, almost comfortably. The bus is packed, yet the mood is calm. Willem Jan sits in the very front, basically on top of the engine. I am lucky — I get a seat.

Then suddenly a groan from the conductor — the man who walks up and down the aisle, collecting the fares. We are carrying a plastic bottle. That will not do. Other passengers start shaking their heads in concern. Eventually someone explains: single-use plastic is not allowed in the Nilgiris. Bringing it in can result in a fine. 1.000 rupees – around 9 Euros. A significant amount of money by Indian standards. And then Willem Jan asks: So what do we do now? Like a perfectly rehearsed piece of choreography at least five passengers make a sweeping gesture out of the window. Out. Throw it out.

Excuse me — what? For the first time in India I get properly angry. I cannot hold it back. The words tumble out of me. Furious, I hear myself saying very very loudly: “We are seriously supposed to throw the fucking bottle out of the fucking window? What the hell?” Ignoring my little outburst. They smile and press the bottle into my hand so I can finish the water first. Wasting water is not done. Oh. Right. Of course. So I drink. Glare at the faces around me. I am so, so angry.

Since arriving in India there have been two things that irritate me every once in a while. Things I try to meet with mildness, with a genuine desire to understand rather than to judge: The contstant wetness of every single Indian toilet and the pollution. The first one slowly resolves itself with humour and a backup roll of toilet paper. The second does not. Rubbish in waterways, in trees, on grassland. In Alleppey, on the beach, it is literally thrown in my face when a fisherman empties buckets of household waste into the sea while I am in the water. I almost choke from shock.

And now this. To prevent trash from entering the protected area, it must not be brought inside — so, if necessary, it gets thrown out three kilometres before the boundary. And gathers there instead. Madness. The most absurd part: no one is bothered by my anger, my outburst. Quite the opposite. When the bottle is empty I do not even have to throw it out myself. The Indian man next to me smiles, stretches out his hand, and takes the karmic mess upon himself. And as my sense of hurt settles, I see the indian love again. They warned us so we would not have to pay the fine. They were trying to help. And suddenly I no longer know why I feel bad — because I have just become an accomplice to littering, or because I treated everyone around me so rudely.

And it really works – Ooty and Conoor are cleaner. Big signs and waste basquets help with that. And probably also the fine. Plastic bottles can not even be bought here. Instead we have to buy a glass one and one very big container to fill it up – yes, that one is plastic. All across the region, conservation and the protection of endemic flora and fauna are written in capital letters. One of the places where this becomes tangible is the Government Botanical Garden in Ooty.

Developed 1848 under the supervision of the British botanist William Graham McIvor, the garden was originally meant to acclimatise economically useful plants to the hills of the Madras Presidency. Today it spreads over about 22 hectares. More than 600 species of trees, ferns, orchids, shrubs and flowering plants grow here — both native shola species and carefully curated exotics. A fossilised tree trunk, said to be over 20 million years old, lies quietly between manicured lawns. The garden is maintained by the Tamil Nadu Horticulture Department and also serves as a centre for conservation, education and the annual flower show that draws visitors from all over South India.

While I am looking forward to hours of wonderful plant-nerding, Willem Jan longs for a quiet bench in the shade. The second we find. The first proves a little difficult. I miss the small signs on trees, shrubs and delicate little plants — those tiny gateways into knowledge that allow me to fully indulge my inner nerd and actually learn something new. It is beautiful nonetheless. There is an entrance fee. Only a few rupees — and still. Personally, I feel these places should be freely accessible. A people’s place. For the community. I have seen it work in so many countries.

In the end it is not species I will remember, but couples on their Sunday stroll, families in the shade, everyone taking a lot of selfies — the garden as a meeting place, not a collection.

Ooty does not hold us for long, and by the very next day we are drawn further on to the sleepier Coonoor, about 20 kilometres away. Hardly any Western tourists seem to make it here, even though it lies directly on the way up the mountain. The only ones we meet are in our fantastic hotel — panoramic view, Indian breakfast, and a manager who is kindness in person. Gerald does not just organise things — he connects people. It is through him that the hills begin to feel inhabited rather than visited.

Gerald also connects us with the rickshaw driver Kanagaraj, who takes us through the hills of the Nilgiris over the next two days. With him we visit tea plantations and small factories, a strawberry farm, waterfalls, and get a peak into everyday local life here in the mountains. Even more: he shares with us his love for photography by taking a whole photoshoot worth of photos with us – never shy of directing us in precicly the right spot.

In the village of Ketti — often called one of the largest inhabited valleys in the Nilgiris, a wide green basin of vegetable fields, terraced slopes and scattered pastel houses — we nibble carrots straight from the soil at the farm of one of Kanagaraj’s old school friends.

The next stop is the carrot washing facility run by Max the cousin of Gerald — who, the evening before, had simply listened to Willem Jan talk about working on a farm and, without a second thought, said: Then you must see this.

A phone call, a quick word in Tamil, and the next morning a gate opens for us that we would never even have known existed. It is a special everyday magic we keep encountering in India — a country of half-open doors where you are waved in before you have even decided whether you are passing by or staying.

The facilities are a place full of movement and colour. Max walks us through every step and answers every question before it is fully formed, As if time has no meaning in this world, he shares his freely and generously. Even more so he shares not only knowledge about carrots and market prices, but access — to a system, to relationships, to trust.

Farmers rent the installation and bring their harvest here. The carrots arrive in thick jute sacks, freshly pulled from the nearby fields. They are picked out, sent along a conveyor belt, washed, brushed, polished — until they emerge at the other end in a glowing, almost luminous orange. Field workers stand ready to sort by quality. With large round sieves they carry the rolling orange abundance from the belt to the sacks, where it is filled and stitched shut with a heavy needle and jute thread. The grade is marked with a cut of green on top. What I notice: no plastic. Only natural materials for packaging.

The workers are here from 4 a.m. until 2 p.m. Every single day. Most of them come from North India or from Nepal, because the chances of finding work are better here. Once a year they take a whole month off to visit their families — unpaid, of course. Paid holidays or sick leave do not exist — especially not for daily wage labourers. Those who work longer on one farm sometimes negotiate arrangements with the farmers. The wages are unimaginable by German standards. With accommodation and food provided: 800 rupees per day for men, 600 for women. Without: 1200 for men, 800 for women. At best around twelve Euros a day.

Around 200 bags are processed every hour. Each bag weighs 100 kilos. A lot of carrots to be moved in a single day. And all of this while the current market price for carrots is far below what would make the work viable. Forty rupees per kilo for top quality would be good. At the moment it is 25 at best. 15 for lower grades. Not enough to even cover the expenses. Because of the amount of produce that is on the market, it is the normal game. At the same time, the government is pushing to bring in larger corporate players. Right now farms range from tiny 0.5 acres to about 300 acres — but corruption and lobbying work here just as they do everywhere else in the world. Max is not a fan. “There should be level ground for everyone. Not only for the rich. Otherwise the poor stay poor.”

I leave the washing plant with orange dots on my white sandals and numbers in my head that refuse to settle back into the abstract. Kilos, rupees, hours, acres — they all have faces now. The woman who keeps laughing while her hands move faster than my eyes can follow. The young boy balancing a sack almost as big as himself on his head and shoulder. There is pride in the way the sacks are stitched, in the careful sorting, in the rhythm of work that begins before sunrise. When we drive away, the hills fold back around us and the tea bushes return, soft and green and almost decorative. They have been here for centuries. But beneath that postcard beauty I now see the fields of carrots, the rented machines, the migrant lives carried from season to season. Travel does this sometimes: it takes a colour — today it is orange — and turns it into a story you cannot unsee.

On our last evening in Coonoor we have dinner at the nearby waffle place. Nutty Waffy Taffy is run by Arif — single-handedly, lovingly, with the quiet pride of someone who has built something that is entirely his own. He has been living here with his son since Covid. He tells us how grateful he is to this small town for the way it took them in. He came for the sake of the boy’s school. Originally he is from Chennai, but even there he was always drawn to the edges, to places where the air is slower and the nights are darker. The countryside rather than the city. Cooking has fascinated him since childhood. While others collected Panini stickers, he collected recipes.

I order a combination waffle and am allowed to assemble it myself: vanilla batter with apple pieces, butterscotch ice cream, caramel sauce and a peanut crumble. Willem Jan goes for pancakes, thick and golden, with strawberries and maple syrup.

While Arif pours love into the hot iron behind the counter, we browse through bound editions of Indian comics — the ones that retell ancient myths in bright colours and dramatic frames. This is how I learn, in a few quick panels, how Hanuman earns his name: as a child he mistakes the sun for a fruit and tries to swallow it, and later a thunderbolt strikes his jaw — hanu — which leaves him marked and makes him the monkey-faced god we know. A story about strength, devotion and a leap that crosses an ocean. When our plates finally arrive, steaming and fragrant, we understand why Arif found his place in Coonoor so quickly. He has quite simply seduced the town with his creations.

Places become home through people like him — through those who cook for you, tell you why they stayed, and in doing so make you feel, for the length of a dessert, that you belong as well.

We return to Coimbatore on the toy train — the slow, rattling ribbon that stitches the mountains to the plains. The Nilgiri Mountain Railway was begun in 1891 and took nearly two decades to complete, an engineering stubbornness carved into rock and slope until the line finally reached Ooty in 1908. Forty-six kilometres of track, 16 tunnels, more than 250 bridges, and the rack-and-pinion system that allows the little blue train to climb gradients that would make most locomotives give up. Inside, is dark polished wood and time. Benches worn smooth by generations of travellers. Small metal plaques with red seat numbers screwed in. Above our heads, roses in glass, as if someone once decided that even a mountain train deserved a a garden. The carriage clatters in a metallic lullaby: ta-dum, ta-dum, ta-dum.

Around us sits a family from Rajasthan. Within minutes the conversation is open. Where are you going next? Write this down. And this. Their words travel faster than the train, laying tracks into our future. A small, moving waiting room for the next chapter of the journey.

Tea plantations glide past the windows in endless geometry, the bright green bushes clipped into soft waves that follow the curves of the hills. For days we have been moving through them, and yet — compared to the carrots — we have learned almost nothing about tea.

We did visit a tea factory. Green leaves arriving in sacks. Withering. Rolling. Oxidising. Drying. Sorting into grades that differ only in the size of their brokenness. A process reduced to a sequence of rooms, to temperature, pressure, timing. At the end: a sales hall. Shelves of neatly packed boxes, tasting counters, the invitation to buy. After the fields and the stories of the past days it left us oddly numb — as if the soul of the plant had been translated into a commodity language we no longer fully understood.

It makes us laugh a little. All those iconic views and so little understanding. It is Kanagaraj’s voice in the carrot fields that stays with me, not the perfectly framed vistas. Being taken by the hand by someone who belongs — that is worth more than any curated tour, any audio guide, any viewpoint labelled Top Attraction.

The train slows at every bend as if it, too, wants to look. As we descend and the air grows warmer with every curve, I feel a quiet ache. We are leaving the Nilgiris behind — the monkeys on the roadside, the soft cold mornings, the people, the plastic politics that first made me furious and then thoughtful.

The mountains close behind us like a book I was not quite finished reading. But the margins of that book are full of names now. Kanagaraj. Max. Arif. The man on the bus. The family from Rajasthan. It turns out we did not travel through the Nilgiris alone — we were carried.

As I rest my head on the wooden side of the train I see a sign aboth my head: Don’t throw trash out the window. I have to laugh. We came for the hills. We leave with stories that refuse to stay inside their frames.

Leave a Reply to Marianne Smit-weber Cancel reply